Religious authority is satisfying the spiritual needs of villagers by conducting various kinds of public service activities. In essence, this is filled with idealism. But what could not be denied is the fact that they provide "cultural support" which is positive in nature. But, how does this work.

Unlike monks with various religious sects adhering strictly to Buddhism, the various religious authorities do not say reject villagers who want to worship alternative deities. They do their best to satisfy the needs of anyone who comes to them in terms of ultimate and realistic needs.

By propagating Buddhist care, the religious authority strives to create a harmonious cultural atmosphere featuring mutual help.

Buddhism defines human life as "bitter." From this, Buddhism explains how to understand the essence of this bitter life and how to seek happiness within it and ultimately achieve nirvana, the ultimate realism.

Through some 2,000 years of evolution, this theory of Buddhism has grown into doctrines rich in content. In order to make it possible for the public to understand the doctrines, eminent monks of Tibetan Buddhism refined the tenets and guideline for life. They do their best to propagate causality and samsara which they say is eternal, stressing the need to be merciful, give alms and accept humiliation. According to their theory, anyone following these guidelines will be rewarded ultimately. As the ordinary people could hardly turn their backs on family life, the monks encourage them to recite sutras, worship the statues of Buddha, and turn the prayer wheels that will also help them achieve a good end.

As such Buddhist tenets are closely related to daily behavior, the religious authority finds it easy to bring people into the network of "cultural support."

First of all, it organizes the villagers to built religious facilities, such as Buddha halls, dagobas and Buddhist images for public worship. Living Buddha's and eminent monks are also invited to hold a summons ceremony or perform religious rituals in the villages. While this satisfies the needs of the monasteries in their daily life, it also gives satisfaction to the villagers. When one dies in the village, the religious authority organizes rituals for the soul of the departed.

According to Tibetan Buddhism, when one dies, the deceased must go through a 49-day "intermediate existence". Reciting the Bar-mdo Sutra to help the dead to overcome this period smoothly is therefore of utmost importance to the family. This helps create stability and harmony, a boon for village security.

Secondly, in promoting Buddhist tenets such as being merciful, helping others and giving alms also makes it possible for the undertaking of public works and activities, such as social relief for the childless, the sick and the helpless. Local government workers say the religious authority does help with local government relief work.

Different from the style in vogue in giving Buddhist lectures in monasteries, the religious authority encourages the villagers to worship the holy spirits and even demons as the major part of their religious activities. According to religious history, these holy spirits and demons were worshipped by the Bon religion in ancient Tibet. Throughout the ages, they become accepted by Buddhism as well Tibetans, and they exist in an all-pervasive way. Once irritated, these holy spirits and demons will bring disasters to the people, such as hailstorms to damage crops, or sickness, so they must be placated.

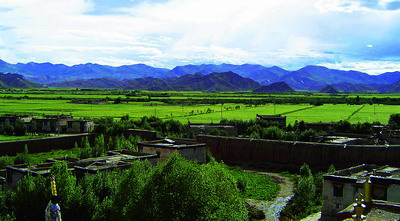

This is why the villagers worship the local deity. In the eyes of the Tibetans, there is a deity in charge of a specific place which may be a village, a tribe, a locality, or the whole region. The Tibetans think the local deity lives in mountains. Hence the Tibetans often worship and take ritual walks around holy mountains. A Lharze or holy palace is therefore built at the top of a holy mountain or at the mouth of a mountain for the deity to stay.

Repeated worship of the local deity encourages them to protect the local people in terms of ensuring bumper harvests and peace.

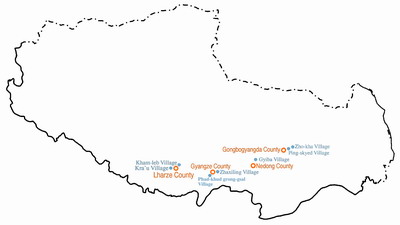

The general behavior is to worship the "residence" of the local deity. Facts prove this works very well. This is why all of the five villages we investigated are doing so. Take Zhaxiling Village as an example it worships at the Lharze twice a year.

The first worship takes place on the third day of the first Tibetan year, and the second soon after the autumn harvest.

At this time, the villagers burn incense, and replace the old facilities in the Lharze with new ones. The villagers' behavior is standardized. They should not offend the mountain god, go hunting in mountains, make loud noises at the mouth of the mountain or fell trees.

The villagers also worship Klu, a kind of spirit residing underground or in water. There are five types of Klu. No matter what kind is involved, the public must worship it carefully, otherwise, one will suffer from more than 420 kinds of diseases such as leprosy and typhoid. As a token of worship, one must not pile up sundry goods, dig and urinate by fountains, and not burn animal hairs and hides in kitchen stoves.

Theoretically speaking, all the villagers are offspring of the deity whose mood affects their life. The villagers worship the deity collectively so as to be more appealing and forceful. This also helps the village heads to organize free welfare work.

"There should be no problem for us to organize each family to produce 40 free days of work," all the village heads say.

From the above we see the religious authority is superstitious but it helps satisfy villagers' need for religious life.