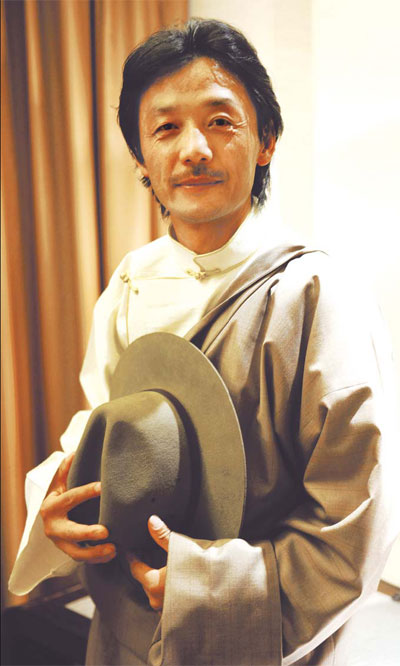

Tibetan author Tsering Norbu won 2010 Lu Xun Literature Prize with his short story The Liberated Sheep. Provided to China Daily

Writer Tsering Norbu says he wants to present the faith, tolerance and courage in Tibetan culture to the world. Yang Guang reports.

Growing up in the neighborhood of Lhasa's Barkhor Street, Tibetan writer Tsering Norbu is all too familiar with the pious pilgrims, the spinning of prayer wheels, the mumbling of mantras, the release of animals for blessings, and the prostrating to the holy sites of Lhasa.

The 46-year-old weaves the mesmerizing world of religion and death in Tibet into his 2010 Lu Xun Literature Prize-winning short story The Liberated Sheep.

A story about prayer and redemption, it tells with sensitivity an old Tibetan's efforts to help his dead wife achieve rebirth.

Plagued by nightmares of his wife tortured in the bardo, the stage between life and death in Tibetan Buddhism, the man saves a sheep from being slaughtered, to earn merit on her behalf.

His increasing religiosity eventually helps him come to terms with his own impending death from cancer.

"I want the real Tibet, the innermost being of Tibetans, and the faith, tolerance and courage in the Tibetan culture to be known to the outside world through my writings," says the humble writer, smiling lightly.

Tsering Norbu used to live in a courtyard house on Barkhor Street, the 1 km-long route that pilgrims take around Jokhang Temple, one of the holiest sites in Tibetan Buddhism. The street, the writer says, now paved with hand-polished stones and lined by stores and venders, is very different from the one of his childhood.

"It used to be a dirt road and business was slack," he remembers. "Nearby farmers occasionally sold wild fruits that were the most delicious snacks for us children."

Tsering Norbu was drawn to literature toward the end of the "cultural revolution" (1966-1976). At a time when literary works were not easily available, he would borrow the "red classics", such as The Red Flag Chronicle, from his uncle.

He enrolled in Tibet University in 1981 to study Tibetan literature, but found his enthusiasm lay more in the Chinese translations of Western poets, such as Shakespeare, Shelley and Byron.

Upon graduation in 1986, he published his first poem Ode to the Night, written in Chinese and modeled after Keats' Ode to a Nightingale.

"I decided to write in Chinese because I wanted to introduce my native land to a larger audience," he says.

After graduation, he taught in a secondary school in Qamdo for two years, before returning to Lhasa to teach at a vocational school.

One day, on his way to visit a relative, he saw an old man crossing a river in a cowhide boat. He suddenly felt inspired to resume writing.

He produced a short story, with the protagonist based on the boatman, and got it published in Tibetan Literature, Tibet's only literary magazine, in 1992.

Though still a fledgling writer, he received great encouragement from his editor, literary critic Li Jiajun. "This gave me confidence and hardened my resolve to continue writing," Tsering Norbu says.

He then worked for 10 years as a journalist and editor of Tibet Daily newspaper. Since 2005, he has been working as an editor of Tibet Literature magazine.

He considers the real beginning of his literary career to be his 2006 National Annual Excellent Short Story Prize-winning Killer, in which a man from Khampa wanders for over a decade to look for his father's killer, but abandons his vengeance when he finds that religion has transformed the murderer.

Tsering Norbu attributes the success of the story to his stint at the Lu Xun Literature Academy in 2004. "The training I received there transformed my outlook on what a novel should be," he says.

"Previously my idea was simply to tell a complete story but now I will also consider the message I want to convey to my readers and the best way to deliver it."

Tsering Norbu has clear views about the development of Tibetan literature and the responsibility of some 500 Tibetan writers nationwide.

"In my opinion, the works of Tibetan writers should reflect the pain Tibet has experienced in the process of rapid development," he says.

"History provides a rough account of that experience; literature delineates the nuanced struggle."

He is now working on his first full-length novel, expected to be completed in two or three years, about the history of Tibet from the late 1950s to the 1980s, as reflected in the life of a Tibetan monk.

"My intention is to restore the true history over the years and reveal Tibetans' reflections on life and death," he says.

According to Tsering Norbu, the book will also include the experiences of those who followed the 14th Dalai Lama to flee China in 1959 and have lived in India and Nepal since.

"It may be the first time their stories are told in a novel," he says.