The organisations in charge of painting and manufacturing Tangkas for the Qing Court were the Zhongzheng Hall and the Section for manufacture and Purchase. Located to the west of the Forbidden City, Zhongzheng Hall was primarily used by the Emperor to worship Buddha and many religious services of the Inner Palace were also held there. At the end of each year, when Mongolian and Tibetan monks came to pay homage to the Emperor, they registered with the Ministry for Vassal States Affair together with the Grand Hutuktu stationed in Beijing, and joined in chanting auspicious Sutras to welcome the New Year. After that they walked to Zhongzhen Hall and other important halls in the Imperial Palace to pray for the Emperor. Zhongzheng Hall was one of the most important halls of the Court and the administrative center of the imperial temples as well. It had two functions:⑴ to manage religious services in imperial temples, the activities of lamas (Tibetan Buddhist monks), and the expenditure for Buddhist rituals; ⑵ supervision of the purchase and manufacture of images of Buddha and Thangkas. The second is the focus of this paper.

Due to the strong religious significance of Thangkas', Lamas had to be involved in their manufacture. Zhongzheng Hall was a workshop for lama painters to paint Thangkas. If necessary, Lamas, who were good at making images of Buddha and painting Thangkas in those temples under the jurisdiction of the Section of Capital Lamas Printing Affairs, were asked to enter the Imperial Palace, working there at daytime and going back to their temples at night.

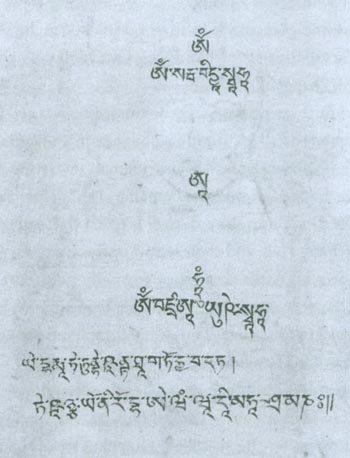

TangKa of Portrait fo Shakyamuni, colored drawing on cloth, in the period of Emperor Qianglong's reign (1736-1795), preserved in the Palace Museum. On the back of the Tangka are inscriptions in Tibetan script

Buddhist scriptures and other instruments used for worship were called 〝Buddha-image painting lamas〞, 〝Buddha-painting lamas〞, 〝painter lamas〞, even directly 〝Zhongzheng Hall Buddha painting men〞. They first sketched a Thangka of the Imperial Court in Zhongzheng Hall, and then sent it to the Emperor for his approval. After that, they formally painted the Thangka after approval or revision according to the Emperor's instructions. Thus, they completed the central part of a Thangka.

The processes of painting Thangkas remained unknown in Han-inhabited areas. During the Yuan and Ming Dynasties, the so-called Thangkas from the interior of China were mainly made on carved silk and woven silk. The genuine court-made Thangkas were rarely seen. Records exist concerning imperial Buddha-painting for altars and usage of paintings from the Western Regions in The Adversaria of Painting and Sculpture in Yuan Dynasty [1], but no formal records of the process of Thangka painting remain. In Yuan Jian Lei Han (a thesaurus compiled the orders of Emperor Kangxi) this kind of painting technique was described as 〝color-painting on white〞. The description if it in Hua-Ji is as follows: 〝Many monks from the Nalanda Monastery in the Central India painted image of Buddha, Bodhisattva and Vajra on Indian cloth. Their images of Buddha were quite different from those in China. They had bigger eyes, strange mouths and ears, a belt across the right shoulder, and were otherwise almost nude. Monk first wrote Buddhist scriptures on the back of the cloth and then painted different colors on the front with gold or cinnabar red as background color. They thought that cow leather colloid was too fluid so they applied peach gum combined with willow juice to the surface of the canvas to make it solid and firm. The Han people had no access to this recipe. When Court Historian Shao was in Lizhou, he learned of some monks coming from the West Regions on some diplomatic mission, so he often asked them to paint Sakyamuni. Today, pictures of the sixteen Arhats are still preserved in the Tea and Horse Administration. [2]〞

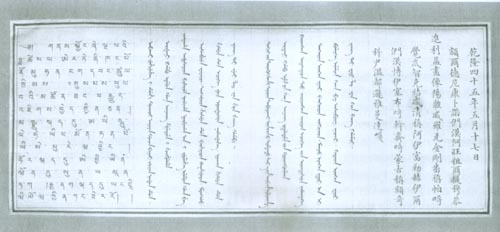

Tangka (Tibetan painted scroll), colored drawing on cloth, tribute presented by the Sixth Panchen on the seventeenth day of the fifth month in the forty-fifth year of Emperor Qianlong's reign, preserved in the Palace Museum. On the back of the TangKa are inscriptions in four languages.

Deng Chun, author of Hua-Ji, remains a mystery to later generations. He probably lived in the period of the Southern Song Dynasty. The period he described in Hua-Ji was likely from the 12th century to the first half of the 13th century. In that period, Naland, the center of Indian Buddhism, was in decline because Islam had destroyed Indian Buddhism at the beginning of the 13th. Therefore, his record was probably from some Indian monks' narration or their memory of the Nalanda Monastery. Undoubtedly, his description of the painting style refers to the painting of Thangkas. Though it was an Indian painting, its brushwork was much the same as the traditional Thangka painting [3]. At the beginning of the Qing Dynasty, this was probably all that the Imperial Court knew about the processes of Thangka painting.

During Emperor Qianlong's region, the making of Thangkas in the Court reached its peak. Tibetan Thangka painting technique was no longer a mystery. The painting technique was no longer a mystery. The painting styles and techniques were not only adopted, but also improved according to conditions in the Court.

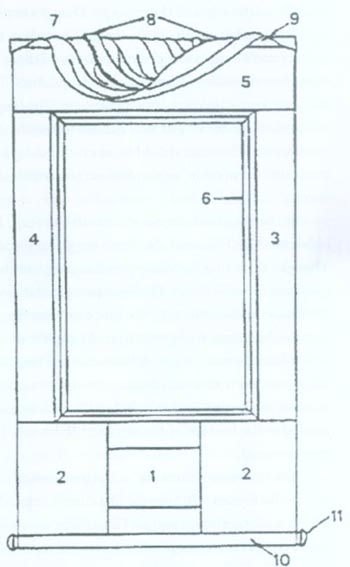

The picture shows the name of the different parts of Tangka