Like all aristocratic families in Tibet, the Khri-smon Family has a history worth tracing. According to theelderly Khri-smon bSod-nams-dpal-vbyor's recollections, the origin of theis family was related to Padmasambhava. In the early period, Khri-smon was located in Vol of Lho-kha, where there is a mountain named "bKra-shis-khri-khang" with a "bZhugs-khri" (throne of Dharma) on the mountaintop. According to the locals, Padmasambhava used it while preaching Buddhist doctrines. bSod-nams-dpal-vbyor believed that even if this family was not directly related to Padmasambhava himself, it was more or less closely connected with him. In Aristocracy and Government last male descendant in the Khri-smon Family and, as a son-in-law, Nor-bu-dbang-rgyal was an eminent aristocratic official but he was not born into an aristocratic family. According to aristocratic endogamy and views on blood relationship, this family should be ruled out of aristocratic families. However, in a sense, Tibetan in Tibet, Mr. Luciano Petech makes an introduction to Khri-smon Family and points out that this family lies in Vol of Lho-kka. Unfortunately, he fails to give a special introduction to its history. According to the author's research, this family was one of the largest aristocratic families in old Tibet, but not very rich. Three members in this family acted as bKav-blons, among whom, Khri-smon Nor-bu-dbang-rgyal "kept this position for such a long time that no one could compare with him in history fo Tibet in this century". In this point, Mr.Luciano Petech's introduction happened to coincide with bSod-nams-dpal-vbyor's recollections. There are many opinions about Khri-smon Nor-bu-dbang-rgyal, but here we are not concerned about what kind of figure he was. The only thing we want to mention is that he was not a genuine descendant of the Khri-smon Family. He used to be the son of a rTsis-pa (bill collector) in a grand aristocratic family Zhwa-sgab-pa, and then he became a son-in-law by adoption in the Khri-smon Family. Later on, he became an aristocratic official and finally acted as a bKav-blon in the capacity of Khri-smon's successor. (See Figure 5)

Figure 5 shows that dKon-mchog-bstan-pa was the aristocrats did not strictly adhere to aristocratic endogamy and blood relationship. Because of this, aristocratic families of this kind were very common, such as; Tsha-rong Family, Ka-shod-pa Family, Sum-mdo Family and others. As mentioned above, Tibetan aristocrats continued their family lineages by way of divorce, remarriage, sons-in-law adoption and son adoption. The continuation of a family was directly related to the existence of male successors. With a male successor, this family's economic position, the social position, would be increased with his promotion to official positions. In the time of dKon-mchog-bstan-pa, Khri-smon Family was already a grand aristocratic family with 2 manors, which created a chance for Nor-bu-dbang-rgyal (not born from an aristocrat family) to become a son-in-law of a grand aristocratic family (Nor-bu-dbang-rgyal was born from rTsis-pa's family (a high-ranking domestic slave) of a grand aristocratic family Zhwa-sgab-pa. Nor-bu-dbang-rgyal Family, not lower than Khri-smon Family in economical position, was an actual agent of this aristocratic family. They were only different in political position. Economic factors resulted in a marriage tie between these two different strata. Soon after he became a son-in-law by adoption, Nor-bu-dbang-rgyal became an aristocratic official in the capacity of Khri-smon's successor. With great effort, he became an eminent bKav-blon. His promotion in power and position brought glory to the fa-mily-what's more, it increased his manor and land holdings. This extension of land increased and strengthened Khri-smon family's social position. However, his second marriage caused the family to fall into an economically awkward situation. Later, Khrismon Nor-bu-dbang-rgyal married bDe-dge master's wife and lived apart from Khri-smon Family, setting up the Khri-smon-zur-pa Family. After this division, Khri-smon Family was on the decline. Nor-bu-dbang-rgyal's ex-wife gave birth to 6 sons and 2 daughters. Because of the decline of this family, 4 boys became monks and the other 2 boys shared one wife. Thus it can be seen that the size of land directly affected Tibetan aristocratic family's social position and fate. By analyzing these three aristocratic families, we can clearly see that the relationship between aristocratic status and land was inseparable.

(4) Functions of Aristocratic Families

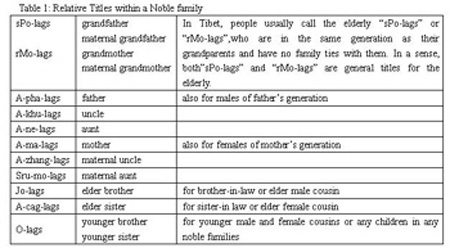

Generally speaking, a Tibetan aristocratic family included not only family members, but also domestic servants and slaves-even its subordinates. All of these members constituted a peculiar family-type aristocratic group. Thus it can be seen that"family" not only served as a life style, but also a social group composed of operating units. Therefore, Tibetan aristocratic families stressed internally persistent units and regarded the use of "we" as a tie to strengthen emotional connections among family members. Meanwhile, family "du-ties" and"obligations" were borrowed to connect family members. As a result they would acquire a natural feeling of "integration" in order to strengthen the group. Tibetan aristocrats usually laid stress on specially designated relations on moral principles-not established on some abstract idea but on a concrete, established organizational pattern. To an aristocratic family's subordinates, loyalty to their masters was vital and to children it was praiseworthy to be obedient to their parents. Following the family group's habitual behavior and stressing its consistency was the method by which an aristocratic family could keep its cohesion and its family members could observe moral principles.

In Tibet, each aristocratic family's structure was fixed in a hierarchy. Various set rules defined each family member's social relations. Around each of them was a comparatively distinct world. Each family member occupied a comparative center in such a vertical estate structure. It is well known that in history Tibet was a feudal, rigidly stratified society. An aristocrat was able to adapt himself to such a hierarchical society for within his family, he was reared to adapt himself to established ideas and practices. In other words, an aristocrat's early experiences and development were completely controlled by his family and he was given so-called "reasonable" behavior modes which would help him more easily cope with estate relations in society. From this point of view, an aristocratic family's major function was to maintain its aristocratic status.

Within a Tibetan aristocratic family, the oldr generation should give children much freedom and tolerance. In any time and in any place, a baby could be given suck and all his behaviors deserved appreciation and tolerance from his elders. These elders began to teach him etiquette until he reached his infancy. After that, the elders increased their restrictions to him. Up to his early youth, he would receive a very strict family education. Heads of the family would teach him to know his rights and obligations, gradually making him understand secular and religious social obligations. In this process, he would know what behaviours were accepted or disapproved of by society. A common saying goes like this: " The pony is father of a good horse, a child's behavior is like a mirror reflecting his future as a capable person." Therefore, each aristocratic family attached great importance to social education in childhood. As a child or a young boy, his spare time, behaviors, senses and emotions were expected to correspond to his family's requirements. When people mentioned an aristocratic member, they seldom focused on an individual. Instead, they regarded him as a representative aristocratic family member. In their minds, an individual was only an element of this family, and his words and deeds as well as virtues all came from the family. For example, before he became Lha-klu Family's successor, Tshe-dbang-rdo-rje was just a small aristocratic family descendant and, in a strict sense, his mother did not come from an aristocratic family. Influenced by his original family's social and economical position, Tshe-dbang-rdo-rje studied in an old private school in Lhasa before he reached the age of 12. His socialization process was completed through his study under the guidance of his teachers. His family only expected him to be an aristocratic official. At the age of 12, Tshe-dbang-rdo-rje's status suddenly changed so he had to reassess his future. In order to make him Lha-klu Family's qualified successor, this family, first of all, ceased his education in the old private school. Then they invited teachers to give lectures to him. In the meanwhile people around him, especially masters and servants in Lha-klu Family, all tried to educate him to be a real successor of this family. In this process, Tshe-dbang-rdo-rje's personal freedom was restricted. He had to practice many rites every day, and the family arranged all his activities. What is more, his amusements had to accord with his family's status14. He was not a direct descendant, but if his words and deeds were in accord with his family's status, his right to succession would not be affected. So within an aristocratic family, no obvious difference existed between sons and adopted sons, but his words and deeds should be in accordance with his family's interests.

(P.S Click on the picture to see large version )

Another example is his elder brother Pha-lha mGon-gnyer-chen-po, who took charge of Pha-lha Family's domestic affairs. He was only an elder brother of his younger brothers and sisters but, like his father, he had a special authority and his brothers and sisters considered his position very natural. In other words, if they refused to accept or violated and neglected this formal order, the entire family would fall into disorder and the family members would feel very embarrassed in society. Therefore, when rDo-rje-dbang-phyug was unwilling to share a wife with his elder brother, in order to prevent him from taking reckless action in response, the family gave him relevant free doms as a repayment for his sacrifice to the family. In such a situation, a concession was made between him and his family. Pha-lha Family neither agreed to his private wishes, nor did it criticize him. He was allowed to keep his private wishes on the premise of not affecting his family's interests. So rDo-rje-dbang-phyug agreed to share a wife with his elder brother for the family's interests. The secret agreement and concession among Pha-lha family members reflected all specially designated human relations in a Tibetan aristocratic family. Such human relationships naturally formed a hierachy, which forced each member to be-have properly and pay a high price to maintain his family's integrity. So an aristocrat fostered in such a family environment knew that he belonged to the family. Due to this belief the family's authority was greatly enhanced in his mind and gradually exerted a subtle influence on him.15

Of course, not all Tibetan aristocratic families adhered to old habits. Taking Khri-smon Family as an example, Nor-bu-dbang-rgyal became a legal successor in the capacity of son-in-law of the Khri-smon Family. Through this, he became an aristocratic official. After that, relying on his intelligence and good fortunes, he became an eminent bKav-blon, which not only made him win personal social and political position, but also consolidated and enhanced his family's social and political position. From a son-in-law, he became a "father" with absolute authority. However, his second marriage destroyed the entire cohesion of the Khri-smon Family. As a "father" he did not meet any obstructions when he chose his second wife but, indeed, he fought for this in isolation. The problem was his choice of sacrificing his family interests to his own. Very soon he had to pay for his "selfish" action. His second marriage forced him to give up the title of "Khri-smon-pa" (Khri-smon Family member). To an aristocratic family, marriage was by no means a simple matter of a sexual union. It exerted a direct influence on a family's cohesion and integration. Nor-bu-dbang-rgyal's second marriage forced Khri-smon Family to accept the division, which would cause land redistribution. In turn, land redistribution not only weakened the entire family's social and political positions but also made him lose the safety and positions as well as wealth that he had gained from his family.16 So an aristocrat had to take such complex and heavy family responsibilities seriously. Considering his family's interests, he must follow his family's conventions (in political and economical affairs) and fit himself into his family and its required behavior perfectly. For a young man, the family offered him a fair, safe, historical position. He was asked to consciously accept the restrictions of the family in such a historical tradition when he became mature... and he was proud to do so. A Tibetan aristocratic family's major function was to maintain an aristocratic status and gain political benefits through economic means. In fact, various aspects are inseparable from a family's functions, from production to consumption, from economy to politics, from culture to religion, from education to entertainments as well as from human reproduction to lineage. Therefore, a Tibetan aristocratic family was multi-functional.