1)Dunhuang Tubo-branch artistic tradition (from the late 8th century to the mid-9th century);

2)The artistic tradition of the "Samada type" in gTsang in the 11th century (the Western Tibetologists as G.Tucci and Robeter Vitali3 considered the wall paintings of Dra-thang Monastery as the continuation and variant of the "Samada Type");

3)A new Indian Pala artistic style appeared in gTsang after the mid-11th century. In addition, some new styles deriving from Hexi Dunhuang art also seemed to appear in the wall paintings of Dra-thang Monastery. Naturally, the diversity of art inheritance does no harm to the ensemble of the wall paintings of Dra-thang Monastery, but this complexity does make its art stand out.

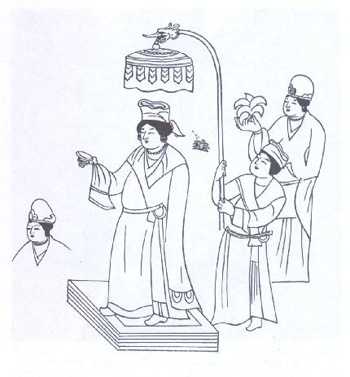

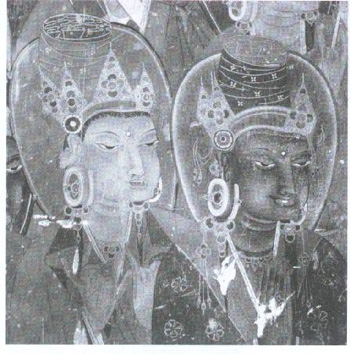

The connection between the two artistic traditions is as follows: in the first place: the proto type of Bodhisattva's crown and dresses in the wall paintings of Dra-thang Monastery can be traced back to either Dunhuang Tubo-branch murals in the early period or Tubo-related paintings in the Tang Dynasty. The Bodhisattv's crown with flattop and a cylinder-shaped topknot made by various kinds of colorful silk cloth, is very unique, and called "kettle-style" (plate 7). The crown can be first found in murals depicting a Tubo btsan-po in Grotto No.159, but it is not so typical as that of the bronze statue of Srong-btsan-sgam-po in the Tubo period (plate 8, preserved in Potala Palace). Srong-btsan-sgam-po's crown is not only cone-shaped, but also with an icon of Avalokitesvara, indicating that Srong-btsan-sgam-po is the reincarnation of the Bodhisattva and the style of topknot is more likely a Tubo btsan-po's headgear. Besides the headgear, Tubo btsan-po's bulky garments with turndown collars have also been put on Bodhisattva in the Dra-thang Monastery. Those garments and robes are mostly made of silk that feels soft, smooth and with splendid colors. The posy designs aligned in the robes with turndown collars were popular styles of attire in gTsang in the 11th century, and they appeared on the costumes worn by mGar-stong-btsan, a Tubo envoy, in the picture of "Marching in a Chariot" by the Tang painter Yan Liben. His pictures on historical events are extremely realistic. What it corresponds to is the bronze statue of Srong-btsan-sgam-po during the Tubo period, and similar medallion patterns are reproduced on the robes with turndown collars: a string of beads with a dragon coiling inside (plate 9). According to G. Tucci, this style of pattern might be the apparel symbols of the aristocracy during the Tubo period. These designs were first seen on bTsan-po's attire and influential officials during the "Former Prosperity of Buddhism", but at the beginning of the "Latter Prosperity of Buddhism", those designs such as dragons or flowers became the symbols of Bodhisattva and Buddha's costumes. In other words, the attires of those sacred figures in the "Latter Prosperity of Buddhism" were modeled after the fashion of those of Tubo aristocrats (plate 10).

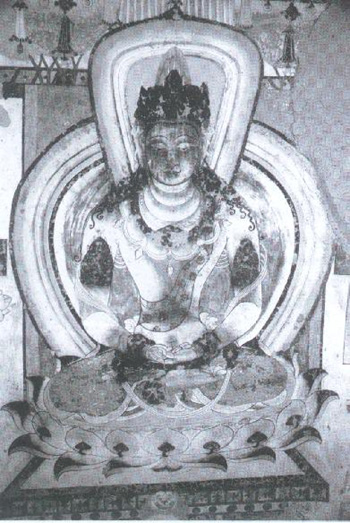

In the second place, Buddha's nimbus serves as another clue to elucidate the relationship between the wall paintings of Dra-thang Monastery and Dunhuang Tubo-branch art. The rich styles of Buddha's nimbus in the wall paintings of Dra-thang Monastery apparently reveal the connection with numerous art schools, and one of them is the inheritance of Buddha's nimbus style from Dunhuang Thubo-branch art. Simple and elegant, the early style differs strikingly from the new Pala style prevalent in gTsang in the 11th century. Characteristically U-shaped, the aureole behind the head and the semi-circular nimbus behind the body form the halo of the Buddha in the early period. Composed of numbers of colorful lines, the aureole and the nimbus are without decorations. This kind of halo seems very unconventional in Dunhuang murals, whose aureole is typically round. In the mid-Tang Dynasty, floral designs of many kinds were also painted in its interior, making the halo remarkably magnificent and complicated. Thus, the Buddha's halo in Tubo-branch art seems simpler (compare the designs in the Dunhuang Buddha's halo with those of the Tubo-branch art, see plate 11 and 12), and a case in point is the halos of the Buddha of Infinite Light and Buddha's Eight Spiritual Sons on the main wall of Yulin Grotto No.25. In the shrines of Dra-thang Monastery, there are two paintings on each side of the main wall (altogether 4), and the Buddha's halo (Sakyamuni) in the centre of each painting clearly resembles that of Yulin Grotto No.25 (refer to plate 12).

In addition, the marble lions below the throne of the Buddha of Infinite Light on the main wall of Yulin Grotto No.25 are also similar in style, even in form and expressive techniques, to a pair of lions which are looking back at each other, rubbing their ears and scratching their cheeks below the throne of the Buddha in each painting in Dra-thang Monastery. Lions arranged below the throne were initiated in the Tubo Kingdom. Under the eaves of the main hall of gTsug-lag-Khang, over a hundred pairs of lions are aligned. Those sacred sites, bearing close political, religious and cultural ties with the Tubo Kingdom, have such auspicious animals as precious lions or white lions. For instance, the well-known lion sculptures standing heroically before the Tibetan King Tombs, the precious lions in front of bSamyas Monastery, a pair of lions in front of Tubo Noble Tombs in Dulan, Qinghai Province and the stone lions on sTan-ma Cliff of Chab-mdo of eastern Tibet and cliff sculptures in Wencheng Princess Temple in Yulshu. It is evident that precious lions were quite a distinguishing subject matter during the Tubo Kingdom, and the geographical distribution of those auspicious lions indicates that the worship of white lions not only prevails in gTsang, but also in Tubo-occupied areas, such as eastern Tibet, A-mdo and Dunhuang in Hexi. However, apropos to the form of the lions, the murals in Yulin Grotto most resemble those in Dra-thang Monastery.

Plate 5 Vairocama, the mural on the eastern wall of Yulin Grotto No.25 (the mid-Tang Dynasty)

Therefore, it is quite clear that the wall paintings of Dra-thang Monastery have inherited the tradition of Dunhuang Tubo-branch murals.

(III)

Apart from the inheritance of the similarities in style of Duhuang Tubo-branch art, the wall paintings of Dra-thang Monastery also absorbed some Han-style elements in patterns, which is obviously the result of the exchanges between different cultures.

Arranged vertically among the flowers below the throne on the right lower part of the main wall in the wall paintings of Dra-thang Monastery is a group of well-known "Attendants in Tang Dress". With round aureole and mysterious gestures, the four attendants are brightly dressed with crowns and exquisite headgears. Obviously, they differ from most attendants in Dra-thang Monastery: 1) some of the figures are turning sideways which is rarely seen in the murals (three quarters of the images are facing front); 2) their topknots as well as the crowns are also distinguished from those of other attendants in the paintings; 3) their location is somewhat special, that is, they are standing below the throne among flowers where usually only two noble lions are seen, while the attendants in other paintings are usually put in the corner. Some researchers infer that those striking differences indicate that those striking differences indicate that they are not ordinary attendants (see plate 13), but more likely the builders of the monastery4 (if it is true, one of them should be Grags-pa-a-gshegs the founder of Dra-thang Monastery). Just as the phrase "Attendants in Tang Dress" we use defines, those four figures have a lot in common with the attendants in the murals in Dunhuang. Their luxury attire, exquisite headgears and even the round aureoles may remind us of the paintings on silk cloth in Dunhuang's Thousand-Buddha Cave. In addition, the designs on the nimbus and aureoles in the wall paintings of Dra-thang Monastery are also similar to those in Qoco and Dunhuang along the Silk Road. The remains of Buddha, the embossed design of the nimbus, flame designs and scroll designs on the walls of the shrine, and particularly the elliptic flame designs of the guardian deities on both sides near the eastern door of the shrine of Dra-thang Monastery can be found in the murals of Bozikelike Grottoes of ancient Qoco and Dunhunag as well.

Besides the specific images, the ensemble of the figures in the wall paintings also points to the influence of the Han art. We've noticed that the figures in the wall paintings of Dra-thang Monastery can be classified as at least of two types, which show two distinctive artistic traditions. The manifestation of the nonnative deities such as Buddha and Boddhisattvas usually follows the Indian Pala artistic tradition, while Tibetan artists will choose different ways of expression for those religious figures such as eminent monks, leaders and Buddhist saints. The wide-sleeved and elegant-pleated robes and the drawing of hair and beard all reconcile with the Han artistic tradition, and this explains why Michael Henss, a German scholar, claims in his article that Buddhist monks in the wall paintings of Dra-thang Monastery have "Chinese faces"5, while Mr. Su Bai believes that the paintings are mostly influenced by the hinterland6.

Plate 6 Tubo bTsan-po Paying Homage to Buddha,the mural in Mogao Grotto No.159 (the mid-Tang Dynasty sketch drawing)

It is no doubt that the wall paintings of Dra-thang Monastery have been influenced by the painting art in the hinterland, however, the question is whether this phenomena was an isolated one in gTsang in the 11th century? Though the relevant archaeological materials are limited, it is definite that the phenomenon is not isolated.

The Tibetan Cultural Relics Survey Team (also the Tibetan Archaeological Team) made a tour to investigate the Iwang (E-Wam) Temple in Kang-dmar County, gTsang area in 1990 and it found some remains of the early statues in this remote small temple. Later in the investigation's report, the Team pointed out that the statues showed some reminiscences of "the Northern Wei to Tang" style of the Central Plains, and dated the statues on the main hall back to the Tang Dynasty7 (see plate 14). It happens that the Italian scholar Tucci drew the same conclusion about the main hall after he conducted a survey on the Iwang Temple half a century ago. He held that Han art had delivered a clear impact on the statues. Surprisingly, though the Chinese Archaeological Team and Tucci, fifty years later, coincidently formed the same judgment on the style, they held totally different opinions on dating. Tucci considered that the statues bearing Han-style should be the remains of the Sa-kya Period in the Yuan Dynasty8, and it seemed to him that it was none other than in the Sa-kya Regime Period that the Han influence was able to permeate in Tibet. Tibetan Archaeological Team's dating appears to have been attributed to the early Tang Dynasty while Tucci's later to the Yuan Dynasty, but the premise of their judgment if probably the same. From Tucci's standpoint, dBus-sTsang between the 11th and 12th century (the Central Plains during the Song Dynasty) was unlikely to be affected by Han art. In other words, the Tang Dynasty (the Team's conclusion) and the Yuan Dynasty (Tucci's conclusion) were both able to see the in-fluence of the Han art, but not the Song Dynasty. However, we are certain that the statues in the Iwang Temple in Khang-dmar County, gTsang area are indeed the artistic relics of the Song Dynasty, and the scholars have confirmed their date as in around 1030 AD after conducting a thorough research and careful study9.

In addition to the Iwang Temple, there were still a number of temples whose styles were identical to those statues in the Iwang Temple in the 11th century. Based on Tucci's two investigations in the 1930s and 40s, the style of the statues in those ancient monasteries, such asrGya-vbur Monastery, rTse-gNas-bza' Monastery and Jo-nang Monastery in gTsang was a combination of Pala and Central Asian artistic styles, which appeared in the early "Latter Prosperity of Buddhism". Western scholars consider the style prevalent in gTsang in the 11h century as the very Pala-Cen-tral Asian artistic style, which is the mainstream we've seen in the wall paintings of Dra-thang Monastery. Besides this, the statues of Four Heavenly Kings preserved in mNyes-thang Monastery located in the western suburbs of Lhasa are of the purer Tang style: the King embracing pipa (4-stringed Chinese lute) are stately but not severe, looking very pleasant and kindly against the auspicious clouds. mNyes-thang Monastery used to be the place where Atisha resided and passed away, therefore it became renowned. If the statues in the main hall of the Iwang Temple bearing the characteristics of "the Northern Wei to Tang" style can be rated as representative relics of Tibetan paintings of the early 11th century, and those of Four Heavenly Kings in mNyes-thang Monastery as the works of the mid-11th century, then the wall paintings of Attendants in Tang Dress, with mysterious expressions, can be regarded as the legacy of the late 11th century. Apparently, the abovementioned three groups more or less had the elements of the Tang style, which continued in gTsang fine arts throughout the 11th century. Its coexistence with the Tang style should not be neglected, that is, the Tang style, just like the early Indian Pala style, is not that pure. It has undergone some developments, so it is more a variant than a transplant of the Tang style itself. Though it strikes some people as familiar, it is not the original. This probably results in complicating the comparison between it and Dunhuang art. Additionally, the statues in the Iwang Temple and the wall paintings of Dra-thang Monastery are the product of quite a mature art, so are the statues of Fur Heavenly Kings in mNyes-thang Monastery.

Plate 7 Bodhisattua's topknot in the wall paintings of Dra-thang Monastery