Late in the 19th century, the Qing Central Government was in a state of permanent decline, and its control over some southwestern and northwestern areas suffered accordingly, making possible British and Russian incursions. In order to expand its sphere of influence and occupy all of Tibet, Britain clandestinely sent nominal preachers, tourists and explorers to explore for minerals in Tibet. Later, they managed to encroach on some of the adjacent countries of Tibet including Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan, paving the way for invading Tibet.

Oil Painting Gyangze Battle.

The First Anti-Britain Fight

In the 1860s, British soldiers, who had occupied Sikkim adjoining Tibet took the liberty of crossing the border at Rina, and scouted toward the northern border near Mt. Lungtog. They alleged that Mt. Nyiang La, which stood to the east of Mt. Lungtog, not Rina, was the actual border between Tibet and Sikkim.

In order to stop British, in 1866, the Gaxag government dispatched a Tibetan army to set up a check post at Mt. Lungtog, prohibiting cross-border trading and preventing any Britain from entering Tibet. What’s more, a White Light Guardian Temple was built on the mountain.

On March 20, 1888, British armed forces comprising over a hundred soldiers launched an assault on the Tibetan army at the foot of Mt. Lungtog. The Tibetan soldiers lined up along the trench saluted the divine image of the Buddha’s protector before valiantly fighting back with their primitive weapons such as spears, bows and swords. A British official was shot dead, followed by a scattered retreat, while there was no casualty among the Tibetans.

Early next morning, British army launched another assault along the same route, which ended with more than 100 British casualties. The Tibetan side lost 20 soldiers in the hard fighting.

When the attack on March 25 broke out, many Tibetan warriors died in the explosion of a bomb lobbed into their midst. They withdrew from Yadong and Pali, and Mt. Lungtog was lost. Later, over 10,000 Tibetan soldiers and militiamen headed for the front to engage in several fights against the British between June and October, but failed to regain Mt. Lungtog.

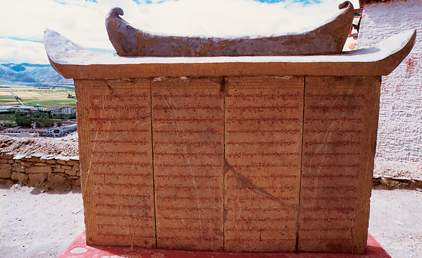

A memorial tablet was erected at Zongshan Hill to remind people of later generation of the Tibetan fight against Tibetan invaders.

The Second Anti-Britain Fight

As a result of this failure, the Central Government signed an unequal treaty with Britain in 1890 under which Sikkim became a protectorate of the British Empire and the British began demarcating and erecting border tablets. In 1893, the Central Government signed an annexation treaty with Britain on matters including mutual trade, regardless of Tibetan opposition. In accordance with the treaty, Tibet was required to reopen Yadong as a trading port, enabling Britain to further encroach on Tibet and control the Tibetan economy under the disguise of doing business. Due to the Tibetan people’s firm opposition, however, none of the articles in the treaty was put into practice, which resulted in British second invasion to seek more benefits.

In June 1902, the British official White in Sikkim led 200 soldiers to Gyigang. Because of the intervention by Tsarist Russia, the troops had to retreat to India, at which time they plundered more than 5,000 sheep and 600 yaks from the Tibetan inhabitants.

The Tibetan government received a missive from the British government in July 1903, in which the latter required Tibetan delegates to be sent to Yadong to negotiate on border issues. The High Commissioner of the Qing Government soon dispatched He Guangxie and Gaxag representatives to Yadong, utterly ignorant of the fraudulent nature of the British claims. The leader of the British invading forces, General Younghusband, suddenly changed the place where the negotiations would be held, and wrote to the Gaxag to send representatives to Gangba Zong near the border with Sikkim to deal with matters relating to trade and border demarcation, with which the Gaxag complied. When they reached their destination, Younghusband and White had already placed six officials protected by 300 soldiers in Gangba Zong on July 11. In reality, all this was a mere stalling tactic adopted by Britain for the sake of preparing for the second invasion of Tibet.

Some 300 British invaders led by Younghusband and White made inroad into Gangba Zong. Picture shows the ruins of the Gangba Castle.

During the months of British occupation of Gangba Zong, they kept moving the borderline between Gangba Zong and Sikkim toward the Tibetan domain, and moreover, they had been scouting and photographing nearby areas. After having drawn the Tibetan government’s attention to these activities, Younghusband abruptly withdrew his troops from Gangba Zong in October, looting more than 20,000 domestic animals from local herdsmen.

After the feint at Gangba Zong, the British invaders quickly assembled forces at Mt. Lungtog. On December 12, 1903, the British force of 3,000 soldiers headed by McDonald and Younghusband, together with the bearers who brought the total force up to 10,000 people, appeared at the pass of Chelilha Mountain and intruded into Yadong’s Rengqengang and Chunpeitang (old customs posts), which controlled the Tang La Mountain mouth at Pali.

With Britain’s occupation of Pali on December 21, they quartered in Pali Zong government office building, and detained the delegates from the Xigaze area for negotiations. Local residents rushed into the Pali Zong government office building with swords, sickles, and wooden sticks to rescue the delegates. Despite being shot, arrested or cauterized by hot irons, none of the Tibetans submitted to the enemy.

On January 4, 1904, Younghusband led a British force equipped with 400 rifles, two cannons and two machine guns to Duina Garwu where he encountered a Tibetan force of 200. From January 12 to February 7, the Tibetan representatives twice requested that Younghusband and his troops withdraw to Yadong for negotiation, which were declined unjustifiably.

Two opinions advocating force and peace emerged in the Gaxag government in the face of the imminent attack. Under pressure from those favoring war, more than 1,000 armed soldiers were sent by the Gaxag.

Two Tibetan army officers--Ladingser and Langserling--negotiating with the British on March 31, 1904 Younghusband (right and with hat) and interpreter (kneeling and speaking).

Under the guise of so-called negotiation, British military forces kept scouting nearby areas and were ready in March 1904 to intrude into Gyangze with sufficient of ammunition for prolonged operations. On March 21, McDonald and Younghusband led nine troops of 1,000 soldiers into the Garwu area with four cannons, machine guns and rifles. As the Tibetan soldiers and militiamen were guarding against invasion in the area, the British requested direct negotiations with Tibetan military representatives.

As the Tibetan party was receiving British representatives on March 31, British troops were stealthily moving into the Tibetan military position, which had been besieged during the negotiations. The British delegate claimed that, in order to show their mutual sincerity for peaceful settlement, the Tibetan leaders should command their soldiers to extinguish the fuses of their matchlock guns and remove the bullets, a request the Tibetans obeyed. But British soldiers reloaded their guns immediately. Younghusband endeavored to hold back the Tibetan commanders in the feigned negotiations, while McDonald instructed his troops to compel Tibetan soldiers to disarm. The British commander ordered his men to open fire after a British soldier was shot down when seizing the guns of the Tibetans. However, Tibetan soldiers awaiting orders were not able to start the harquebus, and the ‘negotiations’ ended in their death.

Over 1,400 Tibetan soldiers lost their lives and only 380 survived the slaughter.

As the British army moved to Gyangze, Tibetan people on the way organized spontaneous attacks. They held up the ammunition and food supplies of the British, blocked the flow of communications, destroyed traffic, and used their swords, spears and clubs to assist the fighting Tibetan forces. The enemy demolished Qamling Monastery and Gungming Monastery, and stripped the hillsides of trees for their fires.

A herder fighting the British invaders.

Zachang was an essential transit point for Gyangze, where there was a one kilometer long canyon with steep cliffs, deep gully and swift river currents. After learning on April 9, 1904 that British troops had already started for the canyon, 4,000 Tibetan soldiers assembled there, ready to protect Gyangze by using the natural defenses.

At midday on April 9, the British vanguard comprising more than 30 cavalry was soundly defeated by the Tibetan warriors.

Heavy artillery was set up outside the canyon to bombard the hillsides. After six hours of arduous fighting, more than 280 enemy soldiers had been shot dead or wounded, and there were 150 casualties on the Tibetan side.

After British invaders breached Zachang on April 10, 1904, they occupied Shaogang the next day, and entered Gyangze. Most of the cavalry and infantry, together with Younghusband’s headquarters, were stationed at Gyannglholing, and groups of soldiers were sent out for patrols and scouting at intervals.

The aggressors also resorted to summoning the leaders and owners of monasteries and manors of the Gyangze magistracy and nearby areas to surrender, but received no response.

After the invaders had been in Gyangze for less than one month, over 10,000 Tibetan soldiers congregated on the roads leading to Gyangze, Xigaze and Lhasa, preparing for battle.

During the first ten-day period of May, British troops dispatched 360 soldiers to raid the Tibetan position at Karula, which was on the way to Nanggarze. Though resisting staunchly, the Tibetans were defeated and fell back on Nanggarze.

Militia men gathered hailing from various parts of Tibet gathered in Gyangze after April 1904. Picture shows two of them.

Meanwhile, only 130 British soldiers were left at Gyangze. On May 3, more than 1,000 Tibetan soldiers attacked Palha under cover of night and struck a crushing blow. Younghusband was nearly killed in this attack. The British army had been at a disadvantage until the troops at Karula withdrew for reinforcement on May 7. A batch of reinforcements left Yadong for Gyangze on May 26 and reoccupied Palha. Tibetan soldiers’ resistance crumbled with large numbers of casualties and the fall of Palha.

Younghusband had no alternative but to break through the tight encirclement with his 40 cavalry to seek help at Yadong on June 6, but was again intercepted on the way.

On June 13, reinforcements composing 2,300 soldiers and eight cannons led by McDonald and Younghusband marched to Gyangze, and reached Naining Monastery in Kangma County on the 25th., which formed a transport stronghold 20 kilometers south of Gyangze. A group of Qamdo militia of 300 soldiers and 500 monks and lay people constructed fortifications around Naining Monastery.

Having anticipated that the invaders were going to pillage cows and sheep, the militiamen in Kangma County organized their strongest members to wear camouflage of sheepskin jackets and lie among the flock of sheep at night and they killed 20-30 invaders at one swoop.

To ensure a clear transit, the invaders dispatched large numbers of infantry and cavalry on a day in late June to assault Naining Monastery from both the south and north. What's worse, they persecuted the monks and laypersons there.

Tibetan militiamen besieged Naining Monastery and made a sneak attack on the British soldiers, who failed to escape.

Before long, British troops mustered all their forces to occupy the mountain behind Zijing Monastery on the morning of June 28, destroying the main hall, nine other buildings and 60 monks’ houses by cannon fire. Cultural relics in the monastery were ransacked by the aggressors, including more than 1,000 gilded copper Buddhist statues, which were 14 centimeters to 4 meters tall. Eventually, they burnt down the monastery.

British troops encircled Gyangze from the east, south and north, blocked the route to Lhasa and Xigaze, and cut off the water supply to Zongshan Hill in Gyangze, preparing for the assault on the city proper.

The 13th Dalai Lama sent representatives to Gyangze on July 1 to negotiate with Younghusband, who proposed that the Tibetan soldiers must retreat from Gyangze by July 5. On account of the Tibetan rejection of this idea, British troops started their attack on the city area of Gyangze on the morning of July 5.

Owning to the fierce resistance from Tibetan army, they suffered heavy casualties. When the stored water on the mountain was exhausted, the defenders let down someone with a rope to fetch foul water from below, and, when that source was drained, they even drank their own urine. But none of the Tibetan soldiers gave in. At the point when Tibetan troops had run out of ammunition and provisions, the British army launched a vigorous offensive. Some Tibetan soldiers broke through the enemy encirclement and shifted to Barkor Monastery to continue the fight. Those who didn’t achieve a timely breakout continued to fight unarmed, and some even died for their country by jumping off the cliffs.

Shortly after the fall of Gyangze Zongshan Castle, Barkor Monastery became the next target, and large numbers of valuable cultural relics and Buddhist scriptures were looted. The major hall for worship was turned into a mess hall for the British army.

Having occupied Gyangze, the aggressors moved toward Lhasa from July 14. Karula Mountain was the necessary passage from Gyangze to Lhasa and was about 70 kilometers to the east of Gyangze, where some 1,000 Tibetan soldiers had constructed fortifications.

On July 17, British vanguard troops went into the ambush ring, resulting in many casualties. Aiming at sweeping away the obstacles to Lhasa, British troops paid dearly at Karub. Some Tibetan soldiers who had no time to retreat stood and fought among the mountains and rocks, and the remaining ones valiantly jumped off the cliffs.

Treaty of Lhasa

On July 19, British troops encountered resistance at Nanggarze after crossing Karula Mountain. The preponderant group favoring compromise among the Tibetan local authorities commanded a retreat and cessation of the fighting, and sent representatives to negotiate with the British army. Nevertheless, the invaders drove straight into Lhasa without considering the request.

The enemy crossed the river straightway on the last day of July, and occupied Lhasa on August 3, taking the aristocrats’ houses and Potala Palace as their headquarters. The Tibetan troops with 3,000-5,000 soldiers that had withdrawn into eastern Tibet raided British army in squads cloaked by night.

Hated by the Lhasa people, and facing severe cold and the soldiers'lack of acclimatization, British military leaders requested a treaty from High Commissioner Youtai, who was a good-for-nothing and immediately compelled the Gaxag to comply with the British request.

The Gaxag had to sign a Treaty of Lhasa with British party on September 6, 1904, which comprised 10 articles, including requirements to open Gyangze and Gartog, in addition to Yadong, as trading posts; paying a war indemnity to the tune of 500,000 pounds, allowing the British army to station troops in Tibet; and qualifying Britain to enjoy the privileges on land, mineral rights and control of telecommunications. However, the Central Government rejected the traitorous treaty since it humiliated the nation's sovereignty, and cabled an order to Youtai on the 14th, requiring him not to sign. On September 23, 1904, the British invaders withdrew back to India, and the Qing Central Government did not sign on the treaty.

In the next year, the Beijing Treaty was signed as a result of mutual negotiation. It proscribed British intervention in Tibetan affairs, and stipulated that other than the Qing Central Government, no other country could have privileges to construct railroads, highways, set up facilities for telecommunications or exploit minerals.

The Tibetan fight against British invasion that occurred 100 years ago eventually ended in failure. But the outstanding achievements Tibetan people made in resisting imperialistic aggression have been recorded in the nation's history.