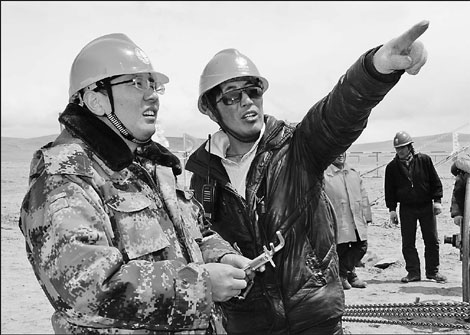

Tashi Dawa, left, a 39-year-old Tibetan engineer working on the Qinghai-Tibet Power Grid Interconnection Project, talks to a colleague at the construction site of a transmission tower at an altitude of more than 4,700 meters in the Tibet autonomous region in June. Provided to China Daily

LHASA - Sheltering from strong winds and a severe snowstorm, hundreds of people huddle inside temporary tents, 4,700 meters up a mountain.

The mercury has dipped well below zero.

They are waiting for the weather to break so they can venture back outside, where they will climb back up 35-meter power transmission towers to finish the important work they are in the middle of.

They are the workers and engineers of the Qinghai-Tibet Power Grid Interconnection Project and the wintry weather is another challenge in their task of connecting Tibet's electricity grid to the State grid.

"The weather is really bad," said Tashi Dawa, assistant chief engineer of the project's seventh bid lot.

Even though the 39-year-old engineer is an ethnic Tibetan, he feels the strain of carrying out such a huge project in such demanding conditions.

The workers see a lot of severe weather and it frequently forces them to pause.

"Our work depends a lot on the weather," he said. "The workers also need to take a break and breathe on the oxygen tanks every two hours because the human body cannot stand such hard work at such a high altitude."

Tashi has been working in the power industry in Tibet for 17 years, ever since his graduation from Wuhan University of Hydraulic and Electrical Engineering.

"I have been offered some opportunities to work in other parts of China where the living and working conditions may be better but I decided to stay here," he said. "I feel that I have a string attached to the Tibetan plateau."

Every power project presents different challenges, he said.

"I love using my knowledge for my home region's development."

The Qinghai-Tibet Power Grid Interconnection Project has been the largest and the most challenging project he has been a part of.

"I feel honored to participate in the project because it will end the long history of Tibet's power shortage, which will help economic development in Tibet," said the engineer.

Tibet has rich water resources that are suitable for hydroelectric generation but the region is heavily affected by the seasons. The hydropower plants run well in the summer when water is abundant but, in the winter, the stations produce little.

Lhapa Dekyi, 25, a Tibetan woman who volunteers at a construction site in Lhasa, said they still have power cuts about twice a week at home.

She said one of her friends went to the cinema three times to finish watching the Hollywood hit Avatar because of all the blackouts.

"I don't have any specific knowledge or skills, so I cannot help with the power transmission tower construction, but I came to the electrical substation in Lhasa to help deliver sand," she said. "I want to contribute."

Lhapa and her fellow villagers have been working at the construction site in Lhasa for two months where the working conditions are better than they are in the mountains.

Up on the mountains, some 1,009 workers and 35 engineers and managers, mostly from outside Tibet, are working on the seventh bid stage of the project.

Motivated as they are, it is not surprising that in recent months, some 240 workers have had to quit because they, as non-locals, could not adapt to the cold and high altitude.

"Each of us has a problem getting to sleep," said Tashi, who explained that the rarified air makes it difficult to stay asleep for longer than five hours.

And their working schedule is tight. The whole power project is scheduled for completion by the end of the year, and the deadline for the end of the seventh bid lot is the end of October.

It usually takes 12 hours to erect a transmission tower, as long as the weather cooperates, Tashi said.

"But, normally, the weather doesn't."

He said most people put in more than 12 hours a day of work.

"I start at 6 am and seldom get to bed before midnight," said the engineer, who shares a 12-square-meter room with two other managers.

But to him the living conditions matter less when he thinks of the people who will benefit from the work they are doing.

"The electricity industry in Tibet has improved greatly in the past years," he said. "It was unimaginable in the past that we would ever be able to take on a task such as the Qinghai-Tibet Power Grid Interconnection Project."

And with the work progressing well despite the challenges, he said he is allowing himself the luxury of thinking about returning home after it is done for a long sleep in a house with abundant electricity.

"I guess all my colleagues share the same hope," he said. "But I'm not complaining. I really love my job and look forward to the day when Tibet's clean energy, including solar power and hydropower, can be delivered to the rest of China and when we can share in their electricity in times of shortage."